The Last Uninstrumented Room

The Last Uninstrumented Room

(

2026

)

On surgery, data, trust, and the gap that defines modern medicine’s biggest blind spot

There is a peculiar asymmetry at the center of modern medicine.

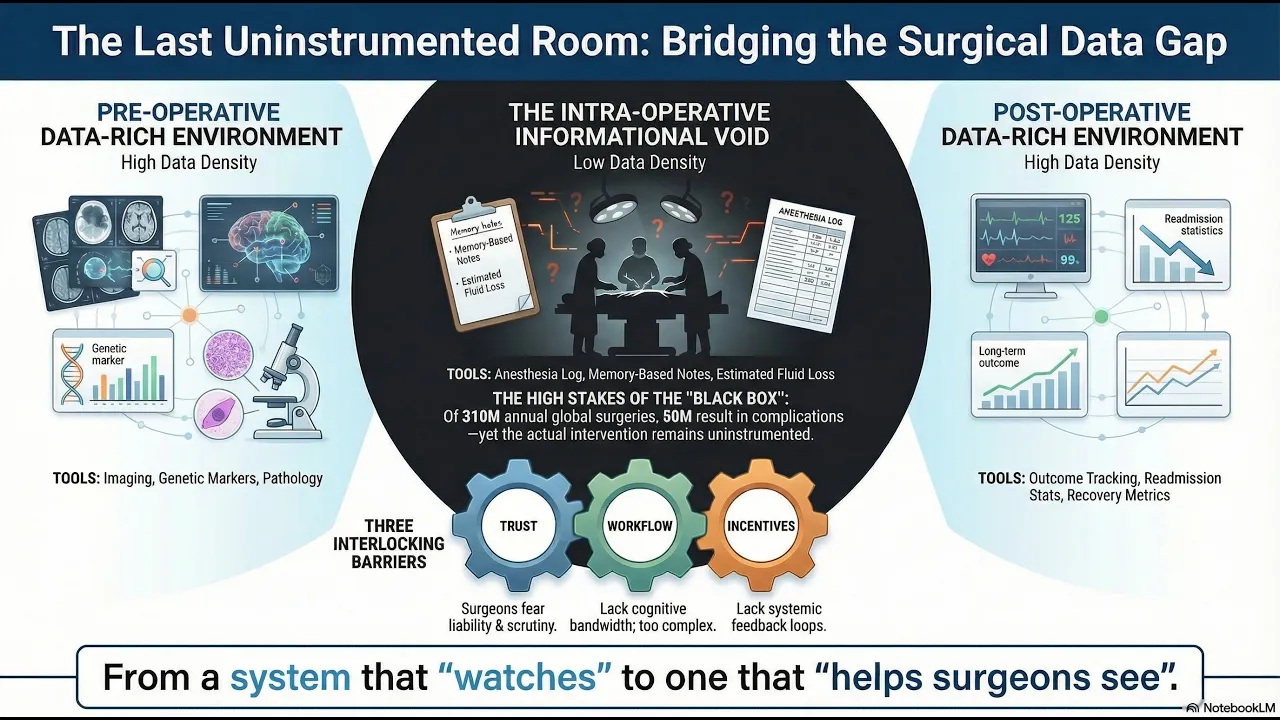

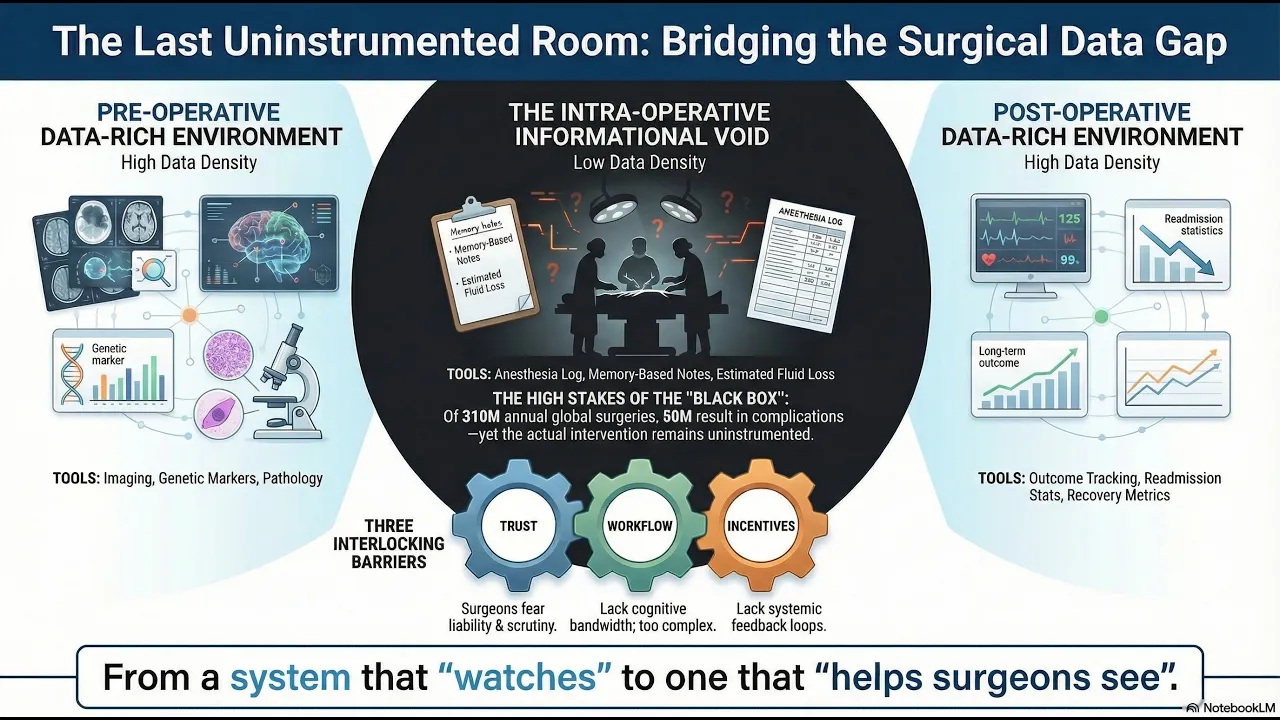

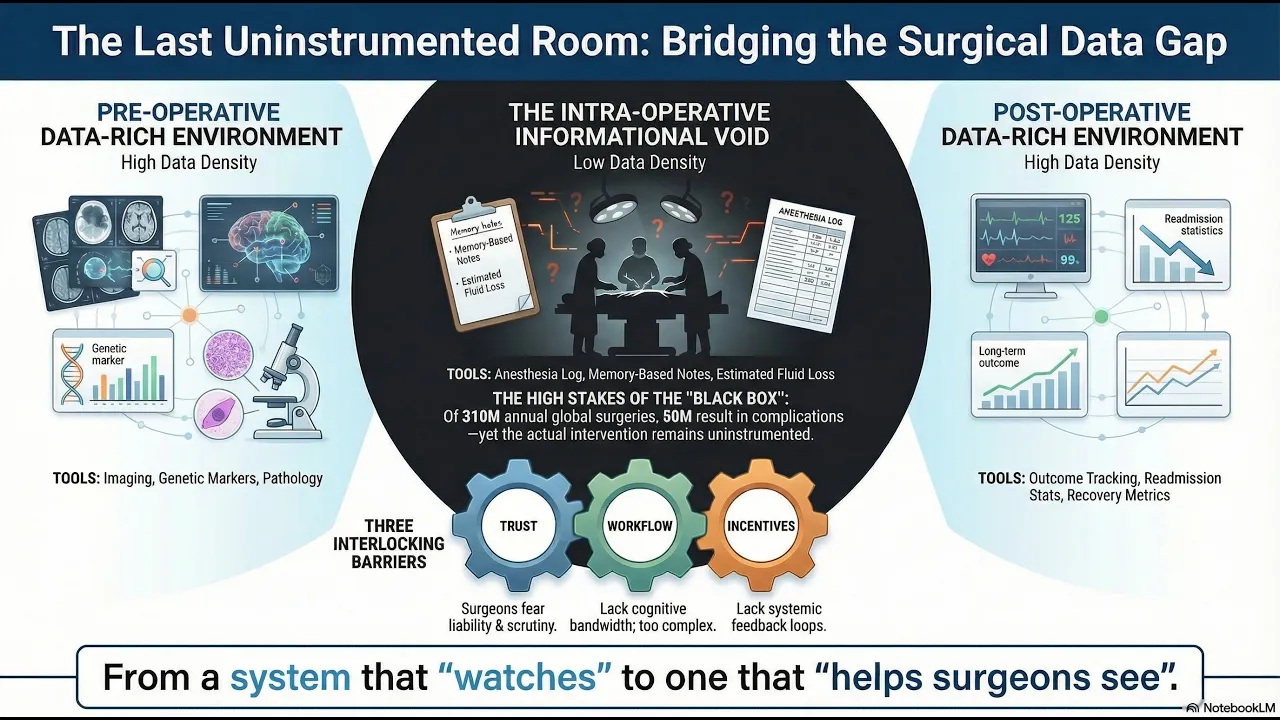

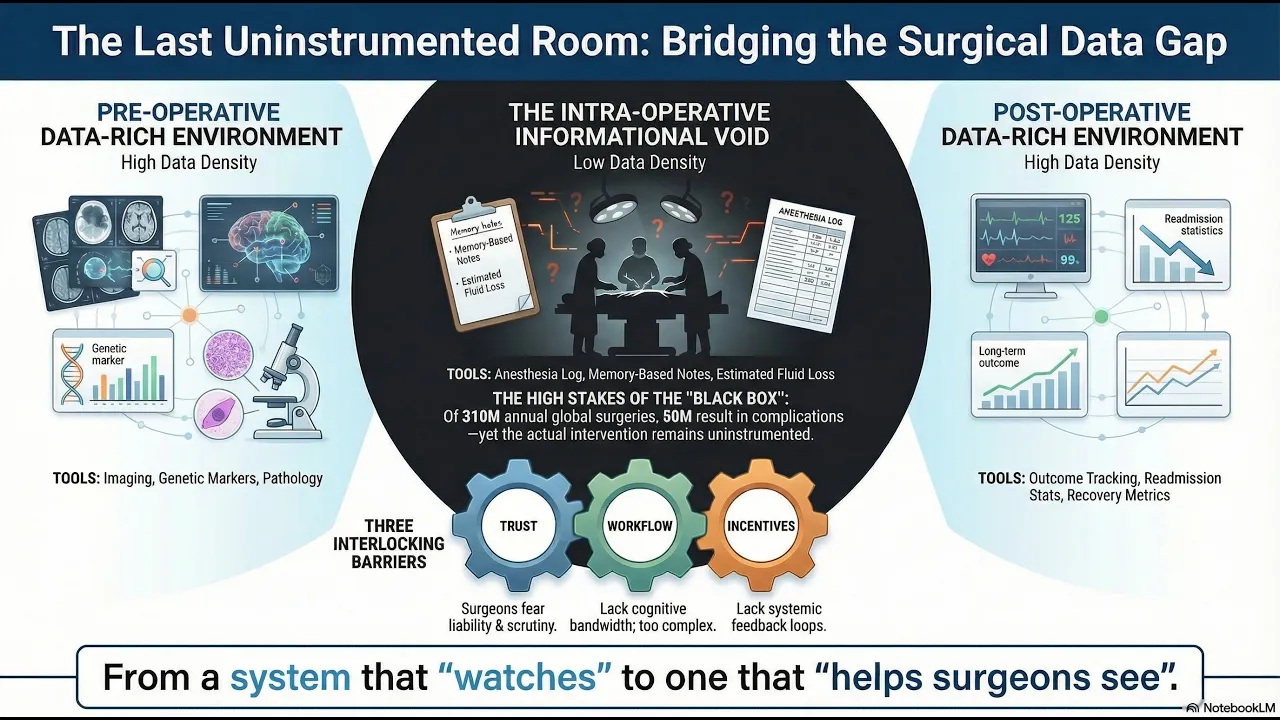

Before a patient enters surgery, their body has been mapped with extraordinary precision. Imaging, bloodwork, genetic markers, pathology reports — a dense, structured portrait assembled over weeks or months. After surgery, another apparatus takes over: recovery protocols, follow-up imaging, outcome tracking, readmission statistics. The pre-operative and post-operative worlds are, by contemporary standards, data-rich environments.

But the surgery itself, the actual intervention, the hours during which a human being’s body is opened and altered, happens in something close to an informational void.

The intraoperative record, in most operating rooms worldwide, consists of an anesthesia log, a fluid balance sheet, an estimated blood loss figure, and a dictated operative note written from memory after the fact. The majority of what happens during a surgical procedure: the sequence of decisions, the technique employed, the moments of difficulty, the anatomical variations encountered is captured nowhere. It exists only in the surgeon’s memory, which is partial, reconstructive, and subject to every cognitive bias that decades of psychology research have documented.

310 million surgical procedures are performed globally each year. Roughly 50 million of those result in complications. The operating room is, by volume and consequence, one of the most important environments in all of healthcare. And it is, by any honest assessment, the least instrumented.

———

This is worth sitting with, because the reasons are not technological. Cameras exist. Sensors exist. Storage is cheap. The tools to record what happens in an operating room have been available for years. The gap is not a hardware problem.

It is a trust problem, a workflow problem, and an incentive problem, layered on top of each other in ways that make the situation resistant to straightforward solutions.

Start with trust. Surgeons operate in an environment of extraordinary personal accountability. A recorded procedure is, in the wrong institutional context, a liability artifact. It is evidence. It is discoverable. Many surgeons have learned, through the implicit and explicit culture of their training, that the less documented about the intraoperative period, the better; it is a rational response to a medico-legal environment that has historically used data against the people who generate it.

Then consider workflow. The operating room is a high-stakes, time-pressured environment where the surgeon’s attention is the scarcest resource. Any technology that requires active engagement like buttons to press, screens to monitor, workflows to manage competes directly with the cognitive demands of the procedure itself. The history of operating room technology is littered with devices that worked well in demonstrations and failed in practice because they imposed even minor friction on the surgical team.

Finally, incentives. There is no systematic mechanism for giving surgeons feedback on their intraoperative performance. Unlike pilots, who receive detailed post-flight debriefs informed by black box data, surgeons largely self-assess. Morbidity and mortality conferences the closest analogue to structured performance review occur intermittently, are limited to adverse events, and rely on the same memory-based operative notes that constitute the original problem. The result is a profession where improvement depends almost entirely on individual motivation, self-awareness, and the luck of one’s training environment.

These three constraints trust, workflow, and incentives form an interlocking system. You cannot solve the incentive problem without data. You cannot collect data without solving the workflow problem. You cannot solve the workflow problem without first addressing trust. And trust, in surgery, is not granted to technologies. It is granted to tools that make a surgeon’s life tangibly better without asking anything in return.

———

There is a historical pattern worth noting here. In aviation, the black box was not adopted because regulators mandated it or because airlines wanted it. It was adopted because, over time, the evidence became overwhelming that flight data recording saved lives and critically, because the data was used for systemic learning, not individual punishment. The technology was the easy part. The trust architecture was the hard part.

Surgery is roughly where aviation was in the 1960s. The procedures are sophisticated. The practitioners are highly skilled. But the system lacks the feedback loops that would allow it to learn from its own performance at scale. Each operating room is, in effect, an isolated instance generating experience that benefits one surgeon, one institution, and then dissipates.

The transformation that aviation underwent from isolated, experience-driven practice to a data-augmented, continuously learning system is the transformation that surgery has not yet made. And the barrier is not that the technology doesn’t exist. The barrier is that the conditions for its adoption have not yet been assembled.

———

What makes this problem structurally interesting is that it sits at the intersection of several irreversible trends.

The first is the global shortage of experienced surgeons, particularly in emerging economies where the surgical burden is growing fastest. The apprenticeship model of surgical training one mentor, one trainee, thousands of hours of observation does not scale to meet the demand. Any system that can transfer surgical knowledge more efficiently has structural tailwinds.

The second is the growing pressure on healthcare systems to demonstrate value. Payers, regulators, and patients are increasingly unwilling to accept opaque variation in surgical outcomes. The question “why does this procedure have a twelve percent complication rate at Hospital A and a four percent rate at Hospital B?” is being asked more frequently, and the honest answer “we don’t have the intraoperative data to know” is becoming less acceptable.

The third is the maturation of computer vision and machine learning to a point where unstructured visual data like surgical video can be converted into structured, analyzable information. This was not feasible a decade ago. It is feasible now, though the gap between technical feasibility and clinical deployment remains wide.

These trends do not tell you what to build. They tell you that something will be built. The operating room will not remain uninstrumented indefinitely. The question is not whether this gap closes, but how and whether it closes in a way that serves surgeons and patients, or in a way that is imposed upon them by institutions optimizing for compliance rather than care.

———

The deepest lesson from studying technology adoption in healthcare is that the tools which endure are not the ones that are most technically impressive. They are the ones that are most honestly useful, the ones that solve a problem the practitioner already feels, in a form they can integrate without rearranging their world.

The stethoscope was not the most advanced diagnostic instrument of its era. But it gave the physician something they wanted: better information at the bedside without demanding anything they couldn’t give. It became infrastructure not because it was mandated, but because it was adopted, one doctor at a time, until practicing without one became unthinkable.

The operating room is waiting for its equivalent. Not a system that watches surgeons. A system that helps them see.

Whether that system emerges from a medical device company, a technology platform, a health system’s internal R&D, or a startup no one has heard of yet, the structural logic says it will emerge. The only uncertainty is whether it will be built by people who understand surgery from the inside, or by people who understand it from a slide deck.

TL;DR